FICHA PRODUCTO

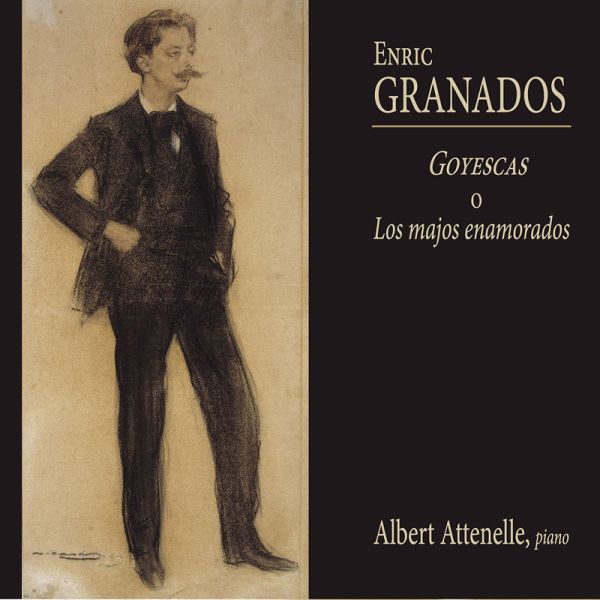

Enric Granados: Goyescas o Los majos encadenados

ALBERT ATTENELE

CD

02/03/2016

CLASSICAL / CONTEMPORARY

COLUMNA MUSICA (COM0346 02)

8429977103460

After recording, successively, Déodat de Séverac’s Cerdanya, Albéniz’s Iberia and Mompou’s Música callada, Albert Attenelle completes this series of mature recordings with Granados’s Goyescas. I think I am being objective when I say that nowadays there are few – very few – performers here or anywhere who could record these cathedrals of 20th-century piano music with the necessary rigour, understanding, versatility, subtlety and expressiveness to recreate each of these works.

The first thing we must do then is to rejoice at Columna Música’s ongoing interest in revising our most cherished piano heritage and at the rare talent of this musician, who has happily devoted the best years of his career to recordings of outstanding quality.

As a direct pupil of Frank Marshall, Albert Attenelle embodies the continuity, vitality and fecundity of the heritage of the Catalan school of piano, which in fact goes back to now mythical names such as Joaquim Malats, Carles Vidiella, Ricard Viñes, Joaquim Nin, Isaac Albéniz or Enric Granados himself, for whom many of these great pieces were written. Works that call for the involvement and the special skills of a type of pianist whose technical training is far above the average for this country.

It’s therefore essential to stress the currency of the important – and decisive – educational task Granados carried out through his pupil Frank Marshall and the academy named after them both. Among the academy’s direct pupils are such famous names as Baltasar Samper, Alícia de Larrocha, Rosa Sabater, Carlota Garriga and Albert Attenelle, not forgetting a whole series of younger performers who ensure and guarantee its continuity.

The work that concerns us today, Goyescas, by Enric Granados (1876-1916), is undoubtedly the composer’s masterpiece. This is the suite for piano Op. 11, composed between 1909 and 1911, dedicated to his wife Amparo Gal and consisting of two books and five pieces. He himself premièred the first book at the Palau de la Música Catalana on 11 March 1911 and the second at the Salle Pleyel in Paris on 2 April 1914. Subsequently, Granados composed another escena goyesca (scene from Goya), El pelele (The Puppet), first performed in Terrassa on 29 March 1914, once again by the composer. Though related to the subject matter of the work, it’s not part of it and shouldn’t be considered a possible postscript either. In fact, it breaks with the formal deployment of the suite in question and takes us back to a late romantic virtuosity whose excesses the composer had, in a way, wanted to shake off and keep away from.

However, the impact and charm of this work were such that they spurred the American composer and pianist Ernest Shelling (1876-1939) to make an opera of it, and that’s how, with the involvement of the librettist and friend of his Fernando Periquet (Valencia, 1873-1940), a work for piano, quite unusually, gave rise to a lyric creation, the opera of the same name, in one act and three scenes, published by Rudolph E. Schirmer and first performed under the baton of the master Gaetano Bavagnoli (1879-1933) at the Metropolitan Opera in New York on 26 January 1916. Its Spanish début took place at the Gran Teatre del Liceu in Barcelona on 9 December 1939.

Unfortunately, though, the success of the New York première (a euphoric Granados told his friend Ricard Viñes ‘I have finally seen my dreams come true… All my present joy I feel more strongly for what is yet to come than for what I have done so far’) was to have terrible consequences. Granados was invited by President Woodrow Wilson to give a piano recital at the White House (Washington), for which reason he put off returning to Barcelona. On 24 March 1916 – at the height of the First World War – the French ferry Sussex he was travelling on from Folkestone to Dieppe sank after being torpedoed by a German submarine in the English Channel.

But what kind of connection took place between Granados and Goya that could help us to explain the spell of this suite for piano? Remember the subtitle: ‘Los majos enamorados’ (The Gallants in Love). Thanks to a letter dated 1910 to his friend Joaquim Malats, we have the composer’s own valuable testimony: ‘I have composed a collection of Goyescas that are of a high standard and great difficulty. They are the reward for my striving to arrive. They say I have arrived. In Goyescas I have found all my character; I fell in love with Goya’s psychology and his palette, therefore of his maja, the lady; of his aristocratic majo, of him and of the Duchess of Alba; of his models, his brawls, his loves, his flirtation. That rosy white of her cheeks, contrasting with the lace and the black velvet with braid fastenings… those bodies with swaying waists, hands of mother of pearl and carmine poised over jet black have captivated me, Joaquín. Well, you’ll see if my music sounds like his colours’.

This, then, is the world of Goya Granados was passionate about: one that revels in combining Tiepolo’s Rococo style with Mengs’s Neoclassicism to produce the best possible decoration for the royal residence. A world saturated with good taste, charme and picturesqueness born out of his work as a painter of cartoons for the tapestries of the Real Fábrica de Tapices de Santa Bárbara (Royal Tapestry Factory): four series of cartoons, of which the second focuses on depictions of popular fun and scenes of country outings on the banks of the Manzanares. This is why Goya’s musical subject matter mainly depicts ordinary people; tapestries or canvases in which the instruments sound in the open air, as in Dance on the Banks of the Manzanares or The Blind Guitarrist, to give just two examples.

However, let’s not look for any exact match between these cartoons and our suite – except for ‘El pelele’, which takes its inspiration from Goya’s work of the same name – so much as the successful recreation of an atmosphere, of a mood, a long-coveted imaginary: the world of the tonadilla, of the sainetes of Ramón de la Cruz – a good friend of the painter – and of Madrid’s urban folklore, its traditional local atmosphere, a whole series of pictures from the late 18th and early 19th centuries of romances between majas and majos in their most ardent and romantic form. One more consequence of the teachings of his master Felip Pedrell, and what we might call a new form of the Spanish musical nationalism of the time (without going further, for Granados Goya embodied more than anything ‘Spain’s representative genius’, so his choice was certainly no accident).

But unlike other works by the same composer, Goyescas transcends this idealised, filigree, joyous world and brings us what I believe is an outstanding synthesis of the luminosity of Goya’s cartoons and the dramatism of the later Caprichos. This is why he gives free rein – so free some people called Goyescas a mere collection of improvisations! – to an amorous passion between a majo and a maja from their first meeting – ‘Los requiebros’ (‘The Compliments’) – to his tragic death – in ‘El amor y la muerte: Balada (‘Ballad of Love and Death’) – and the subsequent apparition of his ghost in the Epilogue: ‘Serenata del espectro’ (‘Serenade to a Ghost’) – and including ‘Coloquio en la reja’ (‘Conversation at the Window’) and ‘Quejas, o la Maja y el Ruiseñor’ (‘Complaint, or the Maja and the Nightingale’).

Perhaps vaguely inspired by the capricho ‘Tal para cual’ (‘Two of a Kind’), ‘The Compliments’ is based on a jota – a more than probable allusion to the painter’s Aragonese origins – whose rhythms divide and interweave with boundless fantasy in an example of the finest counterpoint. In contrast, the ‘Coloquio en la reja’ is a tragic love duet that takes us to a world that is diametrically opposed – the drama is sensed intuitively and foreseen – while ‘El fandango de candil’ (‘Fandango by candlelight’) – based on the tonadilla ‘Currutacas modestas’ (‘Modest Quaintrelles’) and dedicated, by the way, to Viñes – once again shows us a popular atmosphere where dancing and harmonious exuberance reign and where the piano seems to take on the qualities of a guitar. The piece the first book ends with, ‘Quejas, o la Maja y el Ruiseñor’, is definitely the best-known and popular of the whole suite. It’s hard to believe this piano lied took its inspiration, as the composer himself said, from a song heard on the outskirts of Valencia, but whatever the case it’s become a real must in the piano repertory and is even the origin of Consuelo Velázquez’s bolero ‘Bésame mucho’! The fact is that in the middle of a polyphonic plot with four lines in counterpoint, the ardent song of a bird rises up and stands out, singing and singing almost unaffected by the multiple arabesques that try to envelop it, to the point where it becomes the main feature, especially through an onomatopoeic sonority difficult to execute successfully.

Inspired by the tenth of Goya’s Caprichos, the second book begins with the ‘Ballad of Love and Death’, which resumes thematic motifs from the different sections of the first book, as though they all converged there. At first it surprises us with its formal simplicity and the writing without excesses, but even more so with the intensity of the dramatism, which seems to do honour to the fatal dialectics of the binomial from which Goya’s capricho and Granados’s ballad both take their title. Finally, ‘Epílogo: Serenata del espectro’ takes us back to the later Goya, the more visionary and sarcastic Goya, because of the way it conjures up the grotesque appearance of a skeleton who takes hold of a guitar and plays it as he disappears…

The fact is that after finishing Azulejos by his great friend Albéniz (died 1909) and probably stimulated by the staggering international success of Iberia, Granados resumed and quickly completed his Goyescas suite, whose scale and technical ambition surpasses the whole of his previous work. Its melodicism dressed in an aura of improvisation, the arrangement of background harmonies, the original progression of repetitive elements and the endless malleability of its phrasing make it one of the high points of 20th-century piano music. Over and above the ‘accidents of exterior life’ that Carles Riba used to speak of and that seem to condition it, though, the Goyescas suite ranks far above what originally inspired it and now we can hear it freed of almost all its artistic and literary load, as a work of enormous breadth and complexity, shot through with a lyricism at times melancholy, at times glowing, that puts the composer among the postulates of the predominant musical nationalism of the time and possibly even more in the fertile romantic wake of Schumann, Chopin, Liszt or Grieg.

The first thing we must do then is to rejoice at Columna Música’s ongoing interest in revising our most cherished piano heritage and at the rare talent of this musician, who has happily devoted the best years of his career to recordings of outstanding quality.

As a direct pupil of Frank Marshall, Albert Attenelle embodies the continuity, vitality and fecundity of the heritage of the Catalan school of piano, which in fact goes back to now mythical names such as Joaquim Malats, Carles Vidiella, Ricard Viñes, Joaquim Nin, Isaac Albéniz or Enric Granados himself, for whom many of these great pieces were written. Works that call for the involvement and the special skills of a type of pianist whose technical training is far above the average for this country.

It’s therefore essential to stress the currency of the important – and decisive – educational task Granados carried out through his pupil Frank Marshall and the academy named after them both. Among the academy’s direct pupils are such famous names as Baltasar Samper, Alícia de Larrocha, Rosa Sabater, Carlota Garriga and Albert Attenelle, not forgetting a whole series of younger performers who ensure and guarantee its continuity.

The work that concerns us today, Goyescas, by Enric Granados (1876-1916), is undoubtedly the composer’s masterpiece. This is the suite for piano Op. 11, composed between 1909 and 1911, dedicated to his wife Amparo Gal and consisting of two books and five pieces. He himself premièred the first book at the Palau de la Música Catalana on 11 March 1911 and the second at the Salle Pleyel in Paris on 2 April 1914. Subsequently, Granados composed another escena goyesca (scene from Goya), El pelele (The Puppet), first performed in Terrassa on 29 March 1914, once again by the composer. Though related to the subject matter of the work, it’s not part of it and shouldn’t be considered a possible postscript either. In fact, it breaks with the formal deployment of the suite in question and takes us back to a late romantic virtuosity whose excesses the composer had, in a way, wanted to shake off and keep away from.

However, the impact and charm of this work were such that they spurred the American composer and pianist Ernest Shelling (1876-1939) to make an opera of it, and that’s how, with the involvement of the librettist and friend of his Fernando Periquet (Valencia, 1873-1940), a work for piano, quite unusually, gave rise to a lyric creation, the opera of the same name, in one act and three scenes, published by Rudolph E. Schirmer and first performed under the baton of the master Gaetano Bavagnoli (1879-1933) at the Metropolitan Opera in New York on 26 January 1916. Its Spanish début took place at the Gran Teatre del Liceu in Barcelona on 9 December 1939.

Unfortunately, though, the success of the New York première (a euphoric Granados told his friend Ricard Viñes ‘I have finally seen my dreams come true… All my present joy I feel more strongly for what is yet to come than for what I have done so far’) was to have terrible consequences. Granados was invited by President Woodrow Wilson to give a piano recital at the White House (Washington), for which reason he put off returning to Barcelona. On 24 March 1916 – at the height of the First World War – the French ferry Sussex he was travelling on from Folkestone to Dieppe sank after being torpedoed by a German submarine in the English Channel.

But what kind of connection took place between Granados and Goya that could help us to explain the spell of this suite for piano? Remember the subtitle: ‘Los majos enamorados’ (The Gallants in Love). Thanks to a letter dated 1910 to his friend Joaquim Malats, we have the composer’s own valuable testimony: ‘I have composed a collection of Goyescas that are of a high standard and great difficulty. They are the reward for my striving to arrive. They say I have arrived. In Goyescas I have found all my character; I fell in love with Goya’s psychology and his palette, therefore of his maja, the lady; of his aristocratic majo, of him and of the Duchess of Alba; of his models, his brawls, his loves, his flirtation. That rosy white of her cheeks, contrasting with the lace and the black velvet with braid fastenings… those bodies with swaying waists, hands of mother of pearl and carmine poised over jet black have captivated me, Joaquín. Well, you’ll see if my music sounds like his colours’.

This, then, is the world of Goya Granados was passionate about: one that revels in combining Tiepolo’s Rococo style with Mengs’s Neoclassicism to produce the best possible decoration for the royal residence. A world saturated with good taste, charme and picturesqueness born out of his work as a painter of cartoons for the tapestries of the Real Fábrica de Tapices de Santa Bárbara (Royal Tapestry Factory): four series of cartoons, of which the second focuses on depictions of popular fun and scenes of country outings on the banks of the Manzanares. This is why Goya’s musical subject matter mainly depicts ordinary people; tapestries or canvases in which the instruments sound in the open air, as in Dance on the Banks of the Manzanares or The Blind Guitarrist, to give just two examples.

However, let’s not look for any exact match between these cartoons and our suite – except for ‘El pelele’, which takes its inspiration from Goya’s work of the same name – so much as the successful recreation of an atmosphere, of a mood, a long-coveted imaginary: the world of the tonadilla, of the sainetes of Ramón de la Cruz – a good friend of the painter – and of Madrid’s urban folklore, its traditional local atmosphere, a whole series of pictures from the late 18th and early 19th centuries of romances between majas and majos in their most ardent and romantic form. One more consequence of the teachings of his master Felip Pedrell, and what we might call a new form of the Spanish musical nationalism of the time (without going further, for Granados Goya embodied more than anything ‘Spain’s representative genius’, so his choice was certainly no accident).

But unlike other works by the same composer, Goyescas transcends this idealised, filigree, joyous world and brings us what I believe is an outstanding synthesis of the luminosity of Goya’s cartoons and the dramatism of the later Caprichos. This is why he gives free rein – so free some people called Goyescas a mere collection of improvisations! – to an amorous passion between a majo and a maja from their first meeting – ‘Los requiebros’ (‘The Compliments’) – to his tragic death – in ‘El amor y la muerte: Balada (‘Ballad of Love and Death’) – and the subsequent apparition of his ghost in the Epilogue: ‘Serenata del espectro’ (‘Serenade to a Ghost’) – and including ‘Coloquio en la reja’ (‘Conversation at the Window’) and ‘Quejas, o la Maja y el Ruiseñor’ (‘Complaint, or the Maja and the Nightingale’).

Perhaps vaguely inspired by the capricho ‘Tal para cual’ (‘Two of a Kind’), ‘The Compliments’ is based on a jota – a more than probable allusion to the painter’s Aragonese origins – whose rhythms divide and interweave with boundless fantasy in an example of the finest counterpoint. In contrast, the ‘Coloquio en la reja’ is a tragic love duet that takes us to a world that is diametrically opposed – the drama is sensed intuitively and foreseen – while ‘El fandango de candil’ (‘Fandango by candlelight’) – based on the tonadilla ‘Currutacas modestas’ (‘Modest Quaintrelles’) and dedicated, by the way, to Viñes – once again shows us a popular atmosphere where dancing and harmonious exuberance reign and where the piano seems to take on the qualities of a guitar. The piece the first book ends with, ‘Quejas, o la Maja y el Ruiseñor’, is definitely the best-known and popular of the whole suite. It’s hard to believe this piano lied took its inspiration, as the composer himself said, from a song heard on the outskirts of Valencia, but whatever the case it’s become a real must in the piano repertory and is even the origin of Consuelo Velázquez’s bolero ‘Bésame mucho’! The fact is that in the middle of a polyphonic plot with four lines in counterpoint, the ardent song of a bird rises up and stands out, singing and singing almost unaffected by the multiple arabesques that try to envelop it, to the point where it becomes the main feature, especially through an onomatopoeic sonority difficult to execute successfully.

Inspired by the tenth of Goya’s Caprichos, the second book begins with the ‘Ballad of Love and Death’, which resumes thematic motifs from the different sections of the first book, as though they all converged there. At first it surprises us with its formal simplicity and the writing without excesses, but even more so with the intensity of the dramatism, which seems to do honour to the fatal dialectics of the binomial from which Goya’s capricho and Granados’s ballad both take their title. Finally, ‘Epílogo: Serenata del espectro’ takes us back to the later Goya, the more visionary and sarcastic Goya, because of the way it conjures up the grotesque appearance of a skeleton who takes hold of a guitar and plays it as he disappears…

The fact is that after finishing Azulejos by his great friend Albéniz (died 1909) and probably stimulated by the staggering international success of Iberia, Granados resumed and quickly completed his Goyescas suite, whose scale and technical ambition surpasses the whole of his previous work. Its melodicism dressed in an aura of improvisation, the arrangement of background harmonies, the original progression of repetitive elements and the endless malleability of its phrasing make it one of the high points of 20th-century piano music. Over and above the ‘accidents of exterior life’ that Carles Riba used to speak of and that seem to condition it, though, the Goyescas suite ranks far above what originally inspired it and now we can hear it freed of almost all its artistic and literary load, as a work of enormous breadth and complexity, shot through with a lyricism at times melancholy, at times glowing, that puts the composer among the postulates of the predominant musical nationalism of the time and possibly even more in the fertile romantic wake of Schumann, Chopin, Liszt or Grieg.

Preview (30 seconds)

01

00:09:39

Goyescas, Suite para Piano, Op. 11: I. Los Requiebros

02

00:11:19

Goyescas, Suite para Piano, Op. 11: II. Coloquio en la Reja

03

00:06:05

Goyescas, Suite para Piano, Op. 11: III. El fandango de Candil

04

00:06:22

Goyescas, Suite para Piano, Op. 11: IV. Quejas o La Maja y el Ruiseñor

05

00:12:31

Goyescas, Suite para Piano, Op. 11: V. El Amor y la Muerte (Balada)

06

00:08:06

Goyescas, Suite para Piano, Op. 11: VI. Epílogo: Seranata del Espectro

RELATED PRODUCTS